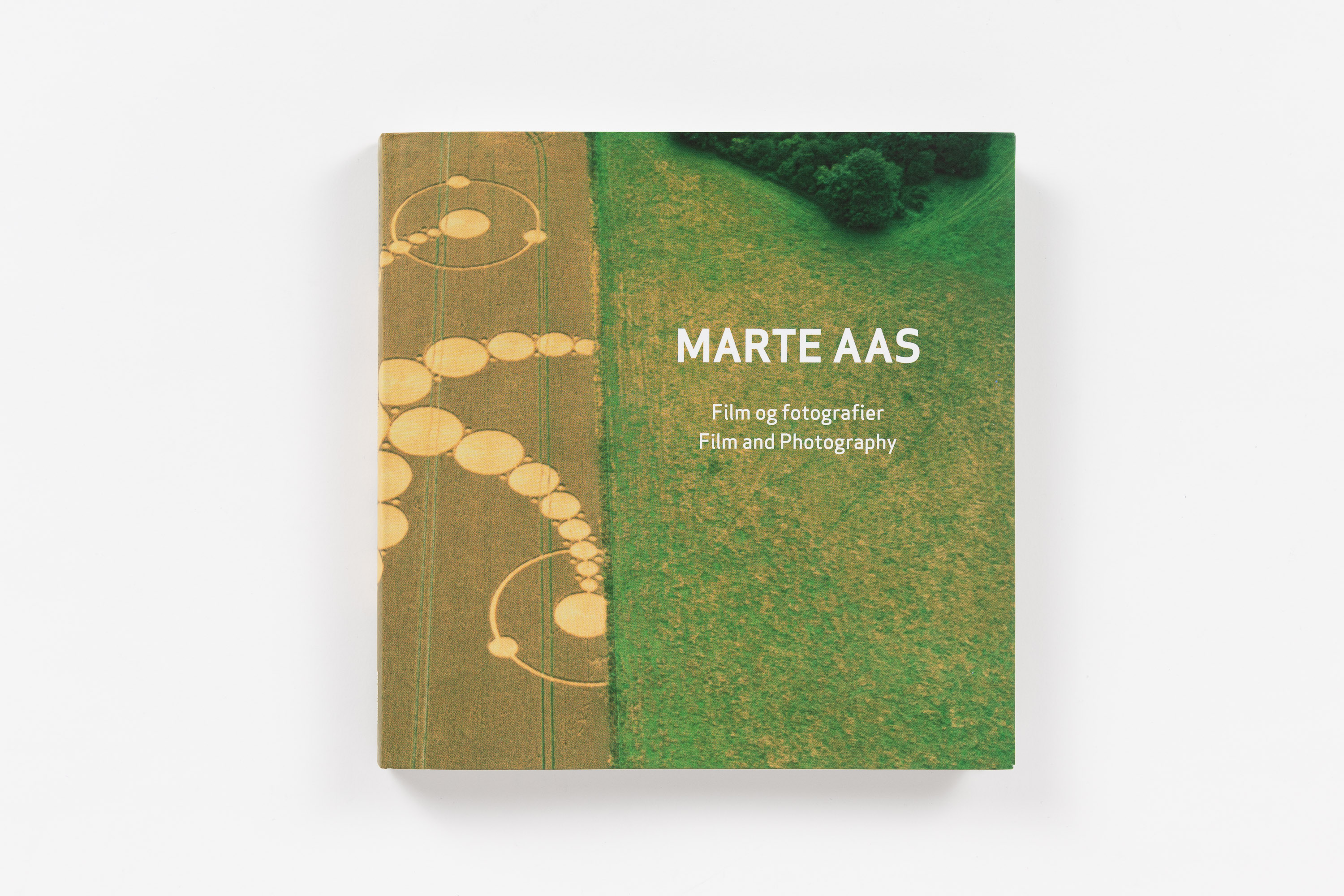

Analogies and Anthologies:

A lexicon for Marte Aas

By Mike Sperlinger

Sentences (on postconceptual art)

A sentence – like an essay, like this catalogue – is a container. But what does a sentence contain? We might say simply: one word after another, perhaps bounded by a period. Perhaps it looks from that perspective like a discrete unit, something definitive. But no sentence, no word, is ‘self-contained’ – every definition, after all, will involve simply more words. What a sentence contains is really a promise, then, of a meaning which it can never fully convey or guarantee. A sentence always bleeds outwards, exceeding its promises, into the deeper reservoirs of language and beyond, into the world which language discloses and yet never exhausts.

Marte Aas’s recent films are full of language and speech, but as works they resist paraphrase. They are not easily contained by language because they want, in part, to address precisely those qualities which leak out of sentences. As Aas herself remarked recently, in relation to the linguistic emphasis of postconceptual art: “There is another kind of knowledge in art, an experience of presence which includes the body and the sensory experience, a knowledge which the linguistic level may struggle to articulate.”

And

One of the distinctive things about Aas’s films is their dreamlike modes of association. Sometimes they may tilt in essayistic directions, but these inclinations are mostly related to Aas’s commitment to remaining receptive: a sailor allowing the tailwinds to set her course, rather than a hunter tracking down a quarry. The voiceovers, when they appear, tell stories in parallel to the images rather than speaking over them or explaining them away. The reassuring, analytical mastery of the traditional (male) essay film narrator is all but absent.

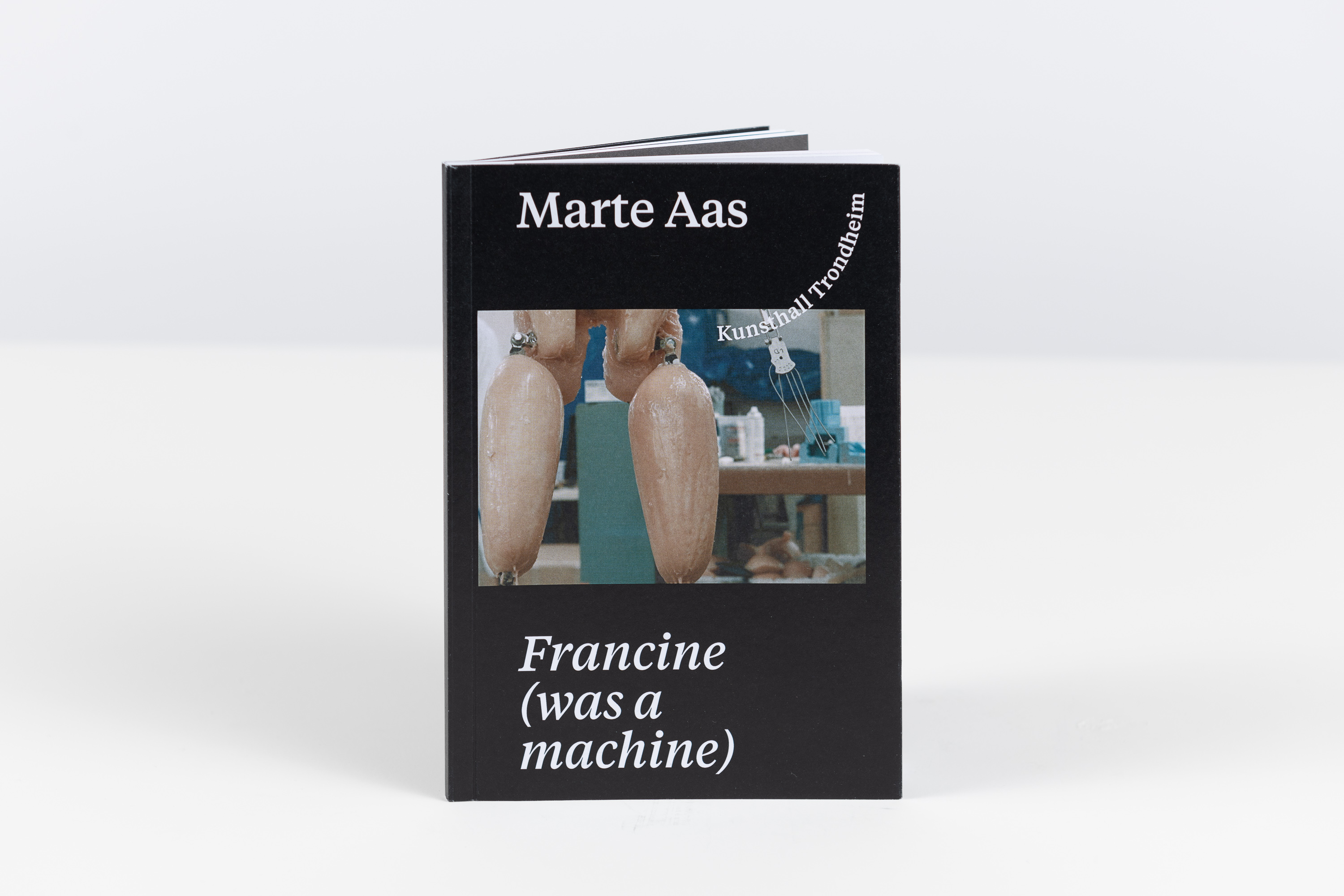

Francine Was a Machine for example, patiently tracks the assembly line of a sex doll factory. Along the way it suggests connections to a history of automata, including amongst others René Descartes’s apochryphal mechanical ‘daughter’, supposedly thrown overboard by alarmed sailors who had discovered her in his cabin. But instead of becoming an elaborate disquisition on automata, the film develops as a bathysmal drift, carried by the sensory and surrealist energies of its images and its soundtrack: the comic and grotesque body parts on workshop benches, in serial form; close-ups of an octopus’s limbs; the muffled, bubbling sounds of being underwater. Where words appear, it is as disconnected phrases which seem refracted, as through water: limbs to tentacles… lungs to gills… becoming and transgressing… The logic is less that of the essay than of the early surrealists, as if Jean Painleve’s zoological films were dancing with Hans Bellmer’s puppets.

This associative method is common to nearly all of Aas’s work: her films thwart our expectations of linear development, instead proceeding by a recursive chain of fascinations, images brought together into constellation by force of their own attraction. This means the films are open-ended too, with a playful sense that the next time you see them a new scene might appear. They are fundamentally additive, constructed with chains of ands rather than buts.

Aboutness

In her wonderful 1986 essay ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’, the science-fiction author Ursula K. Le Guin writes:

Where is that wonderful, big, long, hard thing, a bone, I believe, that the Ape Man first bashed somebody in the movie and then, grunting with ecstasy at having achieved the first proper murder, flung up into the sky, and whirling there it became a space ship thrusting its way into the cosmos to fertilize it and produce at the end of the movie a lovely fetus, a boy of course, drifting around the Milky Way without (oddly enough) any womb, any matrix at all? I don’t know. I don’t even care.

Le Guin’s text tries to unhinge the art of storytelling from its attachment to Heroes and their thrusting, linear, conflict-driven narratives by returning to the latter half of the ‘hunter-gatherer’ formula of early human history. She suggests that containers used to gather (“A leaf a gourd shell a net a bag a sling a sack a bottle a pot a box…”) are a better metaphor than spears or arrows when it comes to writing science-fiction. And intriguingly, she argues this is true both in terms of its potential content (technology as “cultural carrier bag rather than weapon of domination”), but also its form – the novel being a potentially capacious, processual, digressive and inclusive way of gathering narrative: “I would go so far as to say that the natural, proper, fitting shape of the novel might be that of a sack, a bag.”

Aas’s most recent films have taken on the idea of the container explicitly as subject matter. In A Letter to Zoe, the anonymous letter writer continues a one-sided conversation with Zoe about the way everyday life is shaped by containers, from homes to our own bodies, and their inevitable porosities. In the newest work-in-progress, It Cannot Be Contained, the scenes assembled are even more diverse: a design for a self-cleaning house; an interview with a blood plasma entrepreneur; a glass factory; a person’s bare back as they are treated with ‘cupping’… The metaphor of the container is stretched to the point where it is always on the cusp of becoming something else, beyond easy précis – and the question of what kind of a container the film itself is becomes more acute. This latest film seems to ask, more directly than even Aas’s previous work, what is the content of an artwork? How reducible is any work, however photographic, to what it depicts – and why do we insist on this aboutness, a distillable subject matter? What other forms of gathering might an artwork propose?

A few ounces of blood (1)

Aas’s work has always been concerned with the bodily (“an experience of presence”), but human bodies have been relatively absent. Sometimes that absence has itself become thematic, as in the lightly, humorously postapocalyptic What I Miss About People, and What I Don´t Miss About People (2017) in which a dog is the only visible protagonist. Human presence is constantly evoked in all her films, however, both through voiceover and through the persistent sense of the world as somewhere inhabited (from the anthropomorphic personification of the weather in I Am The Weather to the prosthetic body parts in Francine).

In the last two films, however, the human body itself has begun to obtrude, both as a theme and an image. In It Cannot Be Contained, we see extraordinary images of blood microscopy (that vertiginous sense of life-within-life when one sees the motion of blood cells), as well as the sculptural uncanny of the rows of glass vacuum cups attached to a bare back, as the skin reddens and swells.

Jean-Luc Godard once remarked, when accused of having too much bloody violence in his film Pierrot Le Fou, “It’s not blood, it’s red.” In Aas’s work, the movement seems to be in the other direction: away from foregrounding questions of representation and towards a tactile imaginary, an almost interior cinema.

Circlusion

Several years ago, the German feminist Bini Adamczak coined a word: “circlusion”. It is one of those neologisms which names something so everyday, so commonsensical, that you cannot believe in retrospect that a word does not already exist for it:

It denotes the antonym of penetration. It refers to the same physical process, but from the opposite perspective. Penetration means pushing something––a shaft or a nipple––into something else––a ring or a tube. Circlusion means pushing something––a ring or a tube––onto something else––a nipple or a shaft. The ring and the tube are rendered active. That’s all there is to it.

In a sense, all the word names is the process of penetration considered from the inside out:

Let’s say: rotating a bolt into a nut is penetration; and rotating the nut onto the bolt, circlusion... Obviously, both processes are happening at the same time.

For all of the mechanical metaphors, the nipple gives it away: this is fundamentally a way of reframing the way we think about sex – but also all of the other ways we narrate our lives from a male/penetrative perspective (e.g. “getting fucked”) rather than one of containing or enveloping. Like Le Guin’s desire to displace, if only for a moment, “that wonderful, big, long, hard thing, a bone”, Adamczak is proposing a simple but extremely radical shift of perspective. The hope is that this strange word might be the first in a chain of new associations, new possibilities:

No doubt, “circlusion” might end up serving mainly as the kind of formal, technical word one might reach for when talking to a lawyer or a doctor. In bed with a playmate, it might behoove us to develop some kind of snappier equivalent like “gulfing,” “circling,” or “gulping.”

A few ounces of blood (2)

In the eighteenth century, in the midst of a lively debate on the ethics of suicide, the philosopher David Hume wrote:

A hair, a fly, an insect is able to destroy this mighty being whose life is of such importance. Is it an absurdity to suppose that human prudence may lawfully dispose of what depends on such

insignificant causes? It would be no crime in me to divert the Nile or Danube from its course, were I able to effect such purposes. Where then is the crime of turning a few ounces of blood from their natural channel?

For all its rhetorical power, Hume’s question seems to go even further than Descartes in conceiving of human life in mechanistic terms. However, the analogy he draws between the human body and the landscape is unexpectedly resonant.

Seen through the prism of Marte Aas’s work, we might even be tempted to reverse his terms entirely. Her work is deeply interested in the border between the living and the inanimate, for example in its amused but precise attention to the prosthetic body parts of Francine. The cupping treatment in It Cannot Be Contained also returns us to earlier vitalist accounts of human physiognomy and the role of the ‘four humours’, the different bodily fluids (blood, phlegm, yellow and black bile) which supposedly dictated temperament. In such conceptions, the body is really an ecosystem, a climate – a microcosm of the wider environment’s unpredictable weathers.

The human body, in Aas’ films, is an environment, not a machine. An environment is a container, but it is also a kind of infrastructure – those elusive systems which are hard to point to directly, which are somehow without a singular form, but which remain our conditions of possibility. And infrastructures are everywhere in Aas’s work: the circulatory system, the weather, the internet... Moreover, all of them leak into one another, at different scales – no systems are fully closed, no body truly self-contained.

If Hume’s analogy is essentially that a human vein is simply a flow of liquid, morally indistinguishable from a river, Aas’s films seem implicitly to turn it on its head: we should show greater care for the river – and for human intervention into the natural environment generally – not less for the human body.

Anthologising

In a conversation in 2000 celebrating Anthology Film Archives, the legendary experimental film venue in New York – conducted, bizarrely, for Vogue – two of the co-founders Stan Brakhage and Jonas Mekas reflected on how they came up with the name:

Stan Brakhage: Remember, when we were choosing the name Anthology Film Archives, we thought that there should not be the article “the”, because we thought there will be other anthologies and that they would contradict our Essential Cinema list and that would set up a dialogue.

Jonas Mekas: No, that did not happen. We were the only ones who were crazy.

It is true that there was always an inherent tension around Anthology’s ‘Essential Cinema’ list, the risk of an insurgent countercanon ossifying into a new orthodoxy. (Anthology Film Archives was, not incidentally, founded by five men; of the 330 films in the original Essential Cinema list, only five were made by women.) But when it came to the name of the institution at least, perhaps Brakhage and Mekas needn’t have worried so much about the “the”: an anthology, unlike an encyclopedia (or a lexicon), always makes only the weakest of claims to be definitive.

Anthologies, even the most academic, tend to acknowledge their subjectivity – to anthologise is to be self-consciously selective. The word ‘anthology’ has a surprising but revealing etymology in this regard: it derives from the ancient Greek for flower-gathering (from ánthos, ‘flower’ and légō, “I gather”). The earliest usage of term referred to a selection of poems, the analogy being between the poems selected and the most beautiful blossoms – in other words, the anthology was a kind of garland.

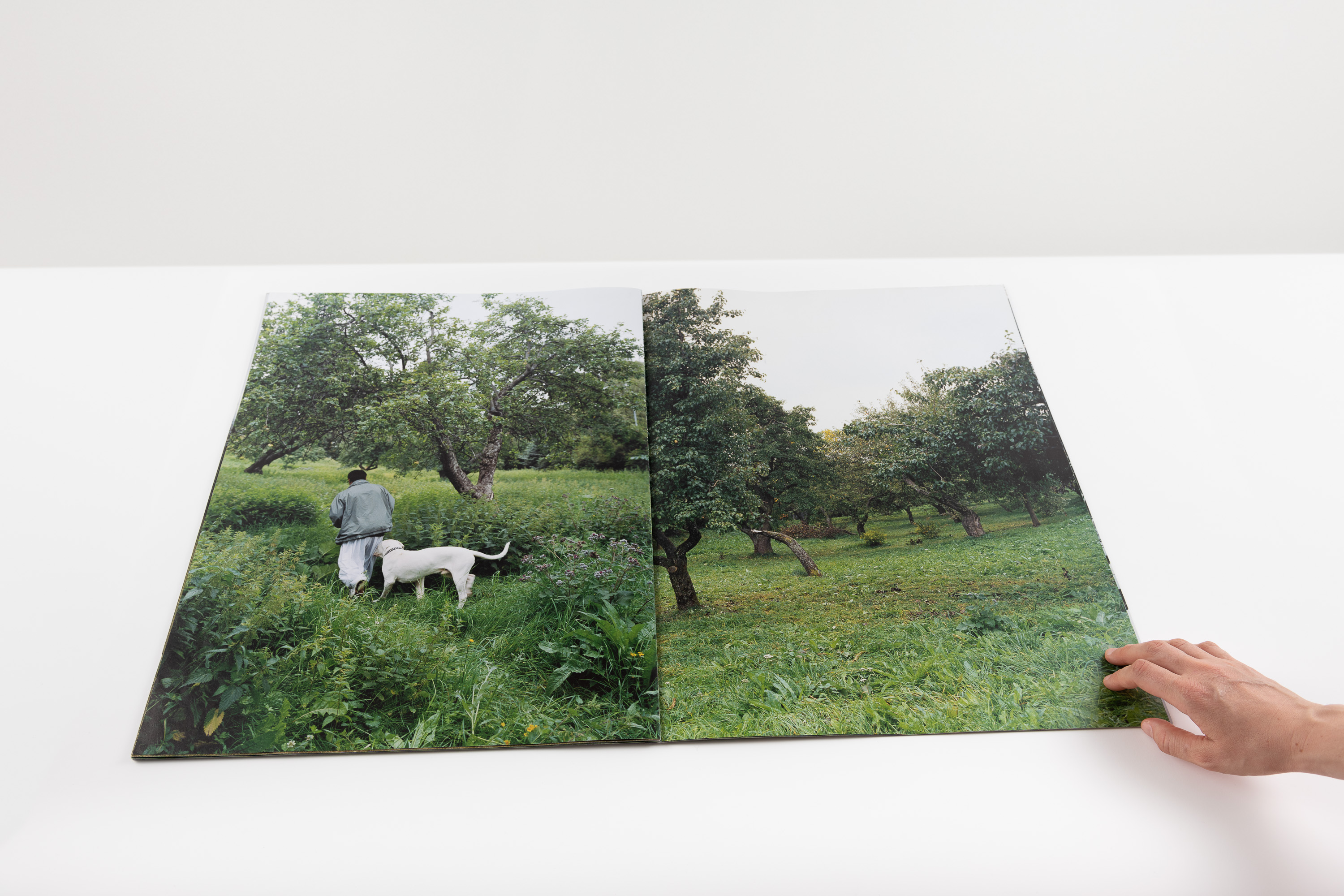

Marte Aas’s films might best be understood as anthologies in this sense, in which every element somehow associatively suggests the next, rather than fitting into any ‘essential’ taxonomic principle. Their acts of gathering are not acquisitive or self-aggrandising, let alone definitive. To put it another way, nothing in Aas’s films is illustrating anything. Their connections are the bonds of curiosity: first Aas’s, and then, as viewers, ours. Hence Aas’s work brings together images and ideas into a form which, like a garland, might have no clear beginning or end – only the infinite loop of what Brakhage himself once called “an adventure of perception”.