Time Travels

Marte Aas´Cinéma

by Jennifer Higgie

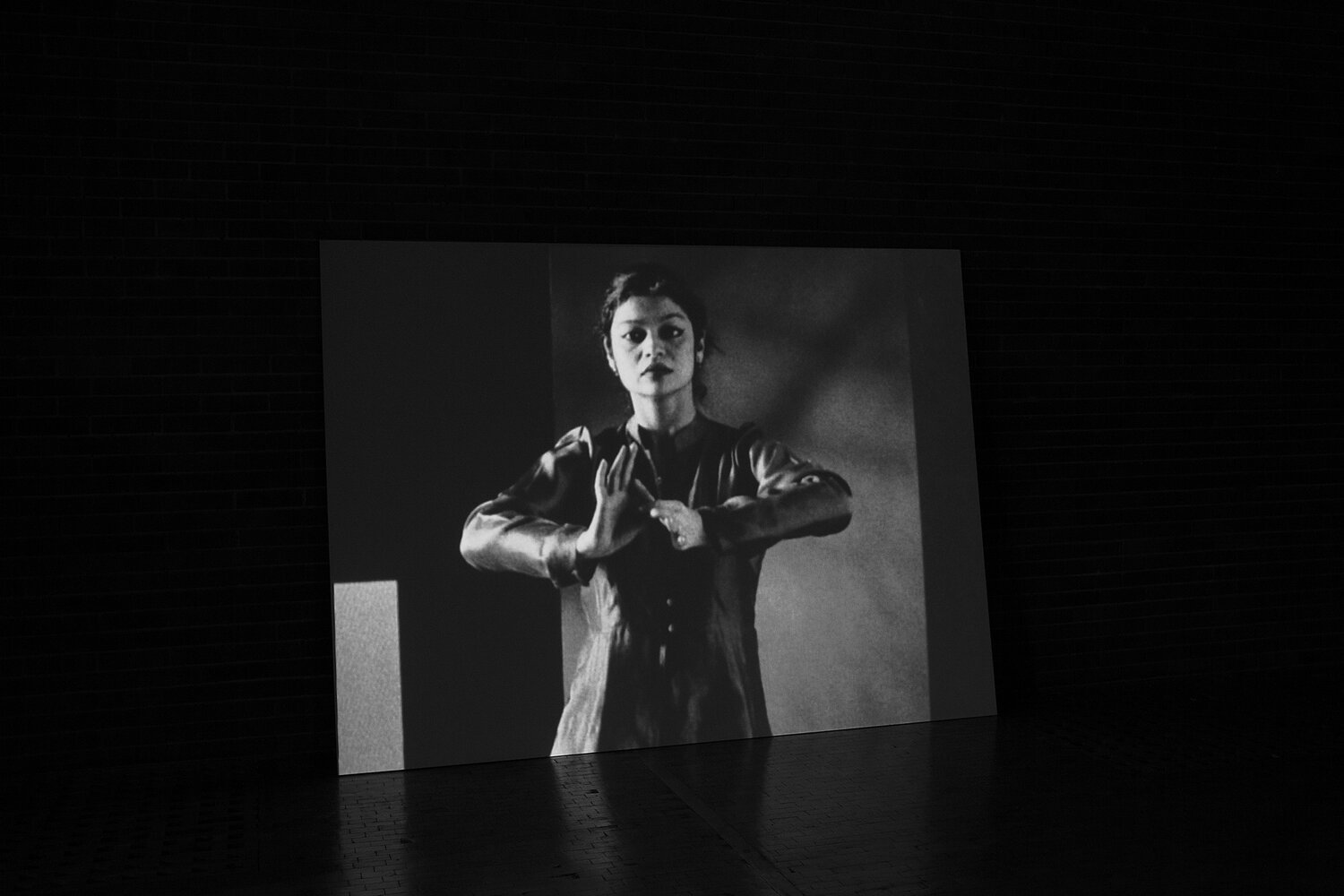

A black screen appears, accompanied by a single, sawing note that ascends and plummets. After a few seconds one word appears: ‘cinéma’, inscribed in a bold, upper-case sans serif typeface that evokes the early days of film. An eye, heavily outlined in kohl, fills the frame, followed by the opaque shadow of two hands dissolving into each other on a wall. The camera pulls back. An impossibly graceful woman, Rukmini Chatterjee, moves with choreographed stateliness in a minimal interior to a haunting film score, written and performed by contemporary Norwegian composer Espen Sommer Eide on an instrument of his own invention, the Consertinome. Chatterjee is performing the ancient dance of Bharata Natyam, which was inspired by the sculptures of the ancient temple of Chidambaram, one of the holiest sites of Hinduism dedicated to Lord Shiva in his form as a cosmic dancer. It is considered to be a ‘fire dance’ – the mystic manifestation of the metaphysical element of fire in the human body. The film is shot in black and white, a reduction that, despite its starkness, is profoundly nuanced (the shades of grey are as delicate as smoke). The camera concentrates on how Chatterjee’s fingers link and separate, a doubling that is echoed in the music (sounds mirror gestures mirror history). Her movements tell a story, but I don’t understand its language, despite being spellbound by the ways in which it is conveyed. This is dance as the incarnation of the tangling of cultural codes; it’s a language resonant with meaning for those who can translate what they are seeing, and for those who can’t, full, nonetheless, of a visceral, visual joy – neither film nor performance punish your ignorance of what it is you are witnessing.

The music builds in intensity; single notes are repeated with increasing frequency and tones become percussive; it is hypnotizing. Then, without warning, the dancer disappears and the image dissolves into dreamy concentric circles – a kind of soft archaic kaleidoscope that evokes smudged charcoal drawings from a distant past. Chatterjee re-appears: her dance becomes more frenetic. At one point, as if to emphasize cinema’s potential for magic and transformation, we see her head and shoulders; she is briefly naked and for a moment stares at us, unsmiling and defiant before being returned to her previous incarnation, clothed and once again vivacious.

This elaborate dance – which takes place in an incongruous modernist setting accompanied by a composition influenced by Norwegian folk music – begs many questions: how can a gesture convey meaning and how specific can meaning be if it is non-verbal? How to pinpoint the significance of how a body moves through space? Does it matter if we don’t understand the provenance of something that moves us? Despite the sheer expressiveness of her movements, Chatterjee’s poses are traditional and considered, her body one in which randomness and improvisation have been banished, a site where, conversely, her individuality shines because of the cultural constraints that encode her. Translation takes centre stage here. From flesh to celluloid, from a time-honoured Indian dance to a contemporary Norwegian artist and composer, to a performer living in France and India, to an Australian writer living in London and writing these words: meaning is passed from one to the other, like a baton in a relay race – a meaning that disperses and relocates in every viewer. Each translates the other along the way, yet no story takes precedent; layers of meaning intertwine as elegantly as the dancer’s fingers. (If cinema is movement, dance here symbolizes cinema; its fluidity, its relationship to time and space, its expressive, encoded potential. The artist looks at the dancer who looks at the audience, each in their own cubicle of geographical and cultural understanding.)

The music suddenly stops; another composition replaces it. The soundtrack now is shrill and repetitive, a kind of psychedelic morse code, as if someone is attempting to communicate something that has become distorted in the act of telling. It is complex and contradictory; a mixture of lament and wild celebration. It could be ominous but Chatterjee’s smile is a joyful counter to any tension the sounds engender. Shadows flicker; her face disappears and returns in the blink of an eye; she almost appears to laugh, but at what is unclear. Her joy in her dancing? At our incomprehension? At the delight she knows we must be taking in looking at her body move?

Cinéma, is, as is now clear, a deceptively simple film. It might initially appear to be an elegant portrait of a woman performing an elaborately ritualized dance, but repeated viewings uncover new levels of significance and complication. This is flagged up from the moment it opens, with the emphasis on its title: the clue lies here in this single word, which was derived from ‘cinématographe’ and coined by the Lumiere brothers in 1899. Its etymological roots lie in ‘kinema’, meaning ‘movement’ and kinein, ‘to move’. So: we have a film, Cinéma, the title of which alludes to the medium’s history and that has as its focus a woman – who, not coincidentally, lives in France – literally moving through space, like the embodiment of the medium that is representing her, employing a choreography that, like cinema, has its own unique history. But this is not all. Marte Aas told me that quite apart from the interest she has in the word’s origins, one of the reasons she chose the film’s title was because the word cinéma alludes to movement, whereas the Norwegian word ‘kino’ is, she feels, ‘static, dry and Calvinistic’. Thus, Cinéma embodies the fact that images resist reduction, tangled as they are with the past, and words have an aural as well as a cultural resonance.

The final moments of Cinéma return to the dancer’s eye before dissolving into a ghostly image of an abstracted eye-like shape. Looking is at the heart of the meandering journey that Cinéma represents: it reiterates how, incapable of time travel, we can only hope to understand ancient belief systems through the filter of our own.

A traditional dancer and new music; an artist in Norway, thinking about the etymology of a word and me here, writing this in my sun-dappled living room in London, all linked in various ways to this brief length of celluloid. This is cinema as movement: the conduit not simply of movement through time, of course, but movement through meaning and space. The possibilities are endless and mysterious.