It flows through us

by Line Ulekleiv

Marte Aas abstracts landscapes – cultural and medial as well as geological. Mainly through photography and film, she has long observed unclarified fields within urban textures, in the blind spots of overall technological development. Aas’ lens has frequently registered the outskirts and inclines of the city, arenas for ‘recreation’ and leisure where modern humanity attempts to recharge. Collective patterns in current infrastructure, ways of life and activities are demarcated unsentimentally, in the interface between cool-headed science and Scandinavian loneliness. Ideas of the future are manifested in visual probes.

Encircling the body

Over the last decade the weight of something more material and bodily has entered Marte Aas’ production, located first and foremost in her five most recent films. Increasingly, she has incorporated sculptural elements, installations that appear as tactile frameworks around filmic narratives. Aas relates consistently to the body as an indefinable combination of biology, technological modelling and mythological narrative: the body is encircled, subjected to negotiation, constantly transformed by expansive and interventional technology.

Mankind is continuously adapting to changing landscapes and environments that work like resonance chambers for variations in the times. The very body of society can be said to be under external pressure, defined more than ever by upheavals and an acute need for resets, new models and alternative mentalities in order to maintain itself. Aas poetically clarifies overarching structures which influence us at various levels: in our everyday organisation of an imminent chaos or quite factually felt on the body, in the flow of the blood.

Element as fragment

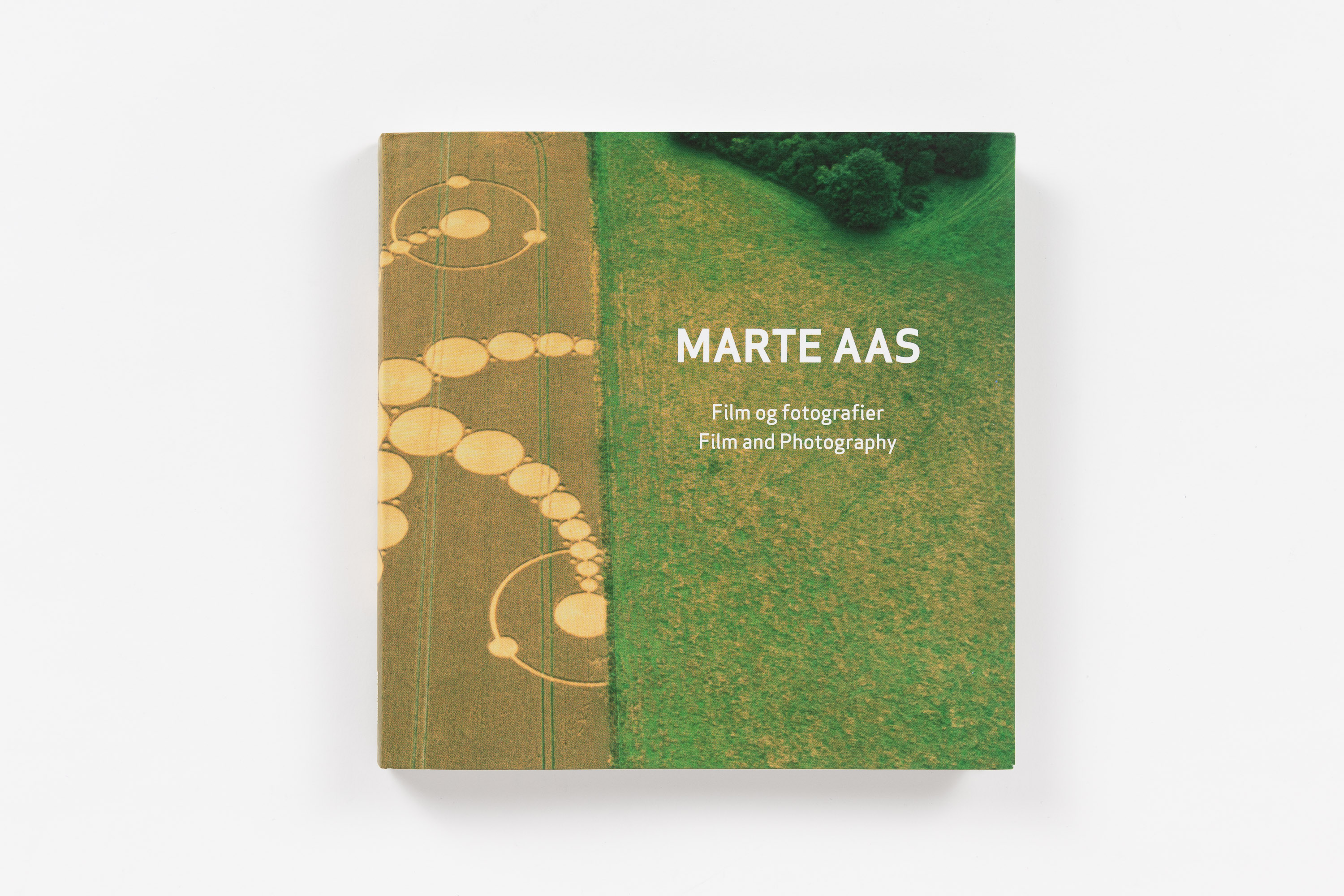

The complex transitions between body and technology are related by Marte Aas to the montage as her preferred type of underlying method. In this book fragments of narratives and implicit information are in constant dialogue with the flow of images – stills from the films, processual sketches and exhibition pictures – and form a spectrum of possible access points. The rhythmic composition of the book supports the fragmented logic of the montage; the thematic fragments expressed in Aas’ films are thus translated into book form in an active expansion of her filmic space. In theory thought, experiment and realised film images are combined and the book can itself be regarded as a physical body or a specific container for the abstract thinking in Aas’ films. The image – as part of the visual storytelling – links up in a fluid, associative way with materially determined statements.

This orientation also addresses Aas’ interest in so-called New Materialism in film, where the assemblage technique demonstrates the different perspectives and scopes of the material. The material basis is deliberately uncertain, and an instability arises among objects, bodies and their representation. Aas tries to link different elements in affective ways, which makes the actual space of interpretation dynamic and mobile. In particular Aas experiments with a soundscape which to a great extent is not illustrative but avoids expected sounds: the sonic creates internal images. The subjective reading of the moving images leads to ever-new accumulations and decodings of information and symbolism. The material self-organises, forms the premises for social worlds, theoretical thinking and human expression. Something is densified, only to drift past the very next moment like some fickle cloud.

Air set in motion

“I am the weather. I am the ocean of air you go around the bottom of. I am the pressure, the humidity, and the rain. I am the wind that reaches your ears. The cold that reaches your skin. The light that reaches your eyes.” The text extract is taken from Marte Aas’ film I Am the Weather (2018), where a voice locates itself among the manifestations of nature – in the red sunset, in the water, in the wind and in the clouds. The various manifestations of the clouds are sketched atmospherically by speech and image: cumulus in tall stacks; feather-like cirrus. The natural components of the air are also constantly addressed as well as an omnipresent technological network – of things like fibre-optic cables, streamline grids, radio waves and Google Maps. In our time the cloud has also become a digital form located in giant data storage centres. Nature is not pure and untouched but entangled in a digital grid adapted to intensive global consumption. In the film, disturbances and contamination are underlined by technical hiss and traffic noise as of a screeching train set. A type of white noise arises that sabotages a passive-romantic empathy with the sublime heavens. The signals are of obscure origin, lost in the electrified matter.

The weather also forces its way into language – the atmosphere speaks in storms and foehn winds, with an applicability to our own mutable mental state. What possesses the voice, the speaking position in the ‘I’ of the title? No religious origin, but a supple projection screen for the fundamental mutability of the cloud. In I Am the Weather the cloud formations become a receptive material, soft cotton tufts seen from a plane where one sits far removed from the world, with a sudden overview. What do clouds look like? Flights of fantasy are panned by Aas, accompanied by electronic music, and pass into things that look like clouds: a friendly wallpaper pattern, a fluffy cat. The airy potential of the cloud can always be filled with the desired substance and mimesis. In her research she took, among other things, the flaming sky in Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) as a starting point: Munch went into a melancholy fit when he experienced that the sky above Ekeberg suddenly turned blood-red. Recent analyses identify this as ‘mother-of-pearl’ clouds that arose as a result of air pollution and specific climatic conditions after a volcanic eruption in Indonesia in Munch’s time. Attention to such causes and effects in nature is forced into being in our own time, faced as we are with great disturbances in the order of nature.

In the work of Aas nature is brought into play – seen through an interwoven scientific, atmospheric and artistic filter which itself forms free circuits. Material units, meteorological phenomena, metaphorical and religious entities: even though clouds have been thoroughly studied, by both science and artists, there is always something that escapes the attention.[1] In the book The Marvelous Clouds (2015) the media scholar John Durham Peters looks at the elements of nature as a technological infrastructure that defines mankind. In his media philosophy he points to the ways in which the natural elements are the source of ecological and economic systems with which mankind and technology have entered into nature and influenced all systems on earth, in the sea and in the sky. When everything from honey-bees to vira and the bottom of the sea are involved, the definition of media is also changed. Peters points to how what we see as traditional broadcasting media (newspapers, radio, TV and the Internet) are relatively new, in the sense that ‘media’ until well into the 1800s referred to natural elements such as fire and earth, air and water. Media are thus both cultural and natural. Infrastructure, originally linked with nature,[2] is in principle a military concept, and has in the past two decades made itself a theoretical point of impact, and reflects greater political and economic changes, including the development of digital networks: “To be modern means to live within and by means of infrastructures.” [3]

The undercurrents

Innovative thinking about resources and an expansion of the human underlie Marte Aas’ practice, in a dialogue with evolutionary biology, ecophilosophy and feminism. Among other things the much-quoted philosopher, feminist and biologist Donna Haraway’s thinking about the coexistence between the human and the machine in our anthropocene age has been significant – for Haraway biology is a flexible starting point with metaphorical qualities: “I have always read biology in a double way – as about the way the world works biologically, but also about the way the world works metaphorically.” [4] Throughout history a cavalcade of models have tried to explain the organisation, behaviour and biological core of the human – today on the whole regarded as curious and antiquated ideas. Aas points firmly in the direction of history understood as mythology and dramaturgical vehicle. In so doing she demonstrates a biological continuity in the need for balance and meaning – the body as veritable storyteller.

The ancient theory of the humours (from Latin humor, which means fluid) was a medical system determined by the various bodily fluids. These had to be in balance, in accordance with the idea of the Greek natural philosophers that all things were created from the four fundamental elements fire, earth, air and water – elements which in the body are represented respectively by the liver, the spleen, the heart and the brain. It was believed that these organs secreted the fluids yellow bile, black bile, blood and phlegm, the four humours considered life-giving in humans, which had to be in good balance to ensure health. It was also thought that the humours could influence individuals’ character traits or ‘temperaments’. If yellow bile was dominant, one was an ill-tempered choleric, if black bile a depressive melancholic, if blood one was high-spirited and optimistic (‘sanguine’) and if phlegm slow-reacting and ‘phlegmatic’. Around 1850 the theory of the humours was superseded by so-called cellular pathology, on which modern pathology is based.[5]

The fire in the blood

The body as an ingeniously arranged system, with internal pressures and real consequences, is viewed as a whole in the work of Marte Aas. Each of the films can be seen as loosely corresponding to its own basic element, bodily fluid and mood, chronologically represented from air to fire via earth to water and back to earth. Certain weather conditions and climates govern the various segments. Something flows through all of us – and the blood? It is a raw material which ties all the components temporarily together, as in a sketch.

In the film It Cannot be Contained (2023) Aas looks more closely at the biological, cultural and symbolic value of blood. It is the vital task of the blood to transport nutrients and oxygen to the cells and metabolic waste products away from the same cells. In our time blood has become a kind of capital; young, pale blood plasma can be injected into old bodies and supposedly extend the owners’ lives – as practised for example by the Californian biotechnological corporation Ambrosia Plasma, which promises its clients that the transfer of young blood can prevent Alzheimer’s and reduce the cholesterol in the body. This is an echo of the vampire myth, where rejuvenation is achieved by tapping an often desirable body, although it is treated scientifically and surrounded by a sanitised and futuristic vapour. The mythological and literary history of the blood is about purity, life force and ideals, but also involves violence, decay and death in an eternal cycle. A montage of approaches in Aas’ films shows how the blood becomes a problematic source of freedom and equality, but also maintains mankind’s ancient desire for immortality. A focus on various landscapes and seasons sorts the episodes, including the myth that the Slovakian countess Elizabeth Báthory (1560-1614) bathed in the blood of murdered young women to reverse the aging process. Here we visit the ruins of her castle, accompanied by a guide.

The Russian philosopher and doctor Alexander Bogdanov (1873-1928) developed so-called tectology at the beginning of the 1900s It was closely linked to revolutionary ideas and is today regarded as a precursor of cybernetics. Bogdanov saw blood transfusions as the most important weapon against aging, but ironically he himself died of an unsuccessful blood transfusion as director of the Soviet Union’s first blood transfusion institute. In 1908 he published the science fiction novel Red Star, a Utopian fable about an advanced civilisation on Mars that uses blood transfusion as a life-extending and equality-promoting resource. For Bogdanov the blood transfusions expressed a reciprocity between two parties, and the idea was that blood was a collective resource that could be transmitted between bodies. Because of widespread anaemia in the Bolshevist leader group, the aim of the blood transfusion institute was much keeping the party leaders healthy.[6] In It Cannot be Contained this literary parallel is thematised in a sequence where a stylised choreography is performed by two dancers in a barren, fissured and Mars-like landscape.

Bogdanov’s theories have today in a way been revitalised, but with an opposite ideological backdrop to his idealistic and collectivist intentions. Within a market-oriented transhumanism life-extending biotechnology and changes in the genetic material will by all indications only be a possibility for the few privileged and well-heeled. Life is no longer a given, but an elastic entity in which you can invest. The result is both hubris and a fundamental uncertainty about what a human being is.

The blood leaves the body and flows around within society. Its reception is normative and linked with race, nationality, sexuality and privilege. Aas interweaves illustrations of bloodletting and microscope images of blood and plasma, as if to map the inner substance of the fluid. She also dwells on ‘The Blood Ban’, when homosexuals in Northern Ireland fought at the beginning of the 2010s for the right to give blood, at a time when risk and fear were associated with a whole group as an after-effect of the AIDS epidemic. This is also how blood donation is practised in Norway today: men who have sex with men are not allowed to give blood. Details of a bluish forest, as if filmed by surveillance cameras, emphasise the forbidden and covert. The film ends in white, in the snow, with the artist Hans Ragnar Mathisen narrating anecdotally that as a young student he sold blood in China for 1200 yen a litre. It was good blood: Sami blood from arctic regions. The diffusion of the blood, its status as both threat and solution, is an unfinished chapter. The blood has a price and the investment is ongoing. Marte Aas draws a historical, ideological and political essence out of this flowing material.

Future earth

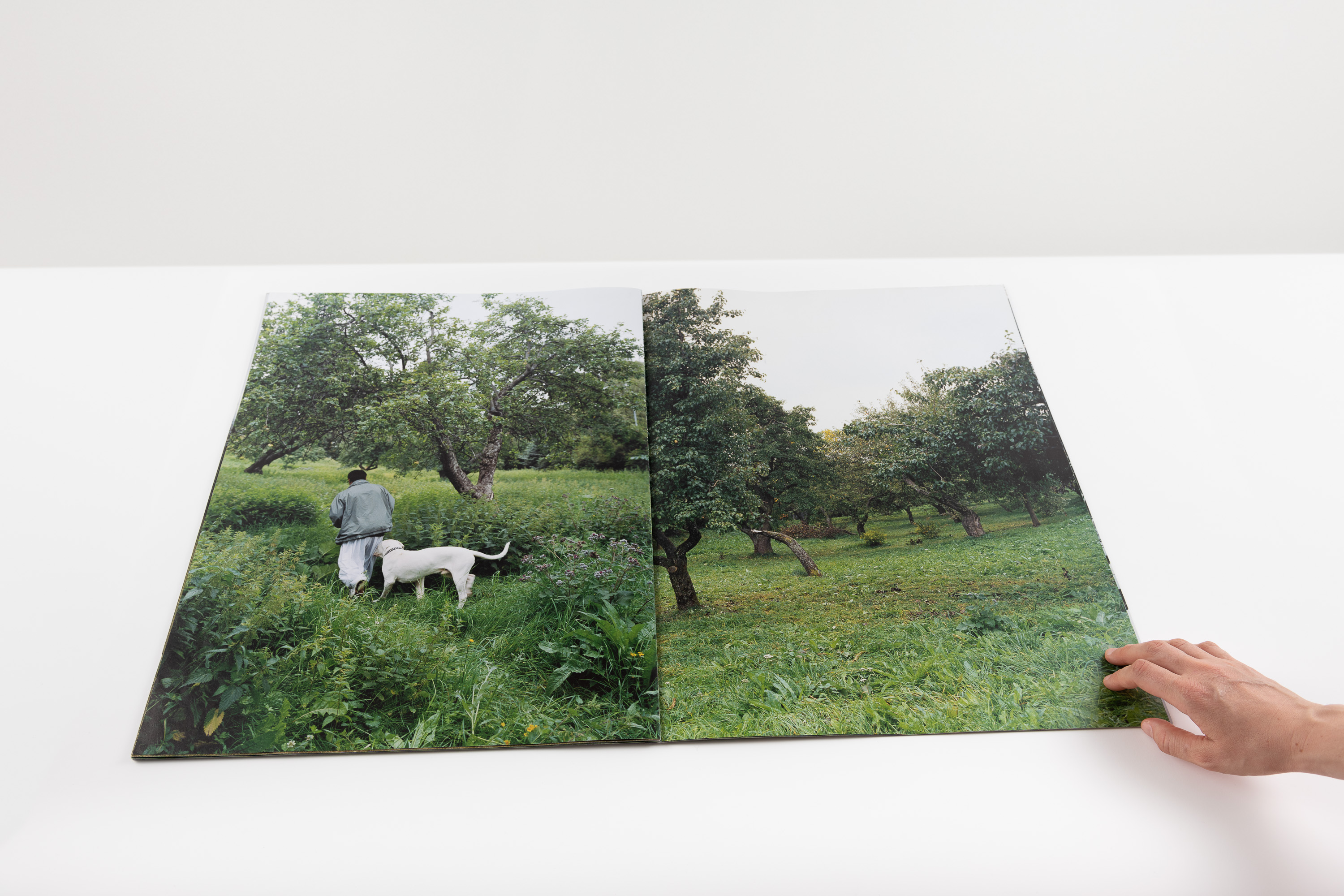

Speculation about what awaits us in the future (personally and collectively) corresponds in the work of Marte Aas to finds from the past, artefacts and episodes that are revealed in many layers. The scenic, where the landscape as geological surroundings becomes a highly charged backdrop for an idea of the future, is manifested very clearly in the film What I Miss About People, and What I Don’t Miss About People (2017) shot in a granite quarry. Here mankind is strikingly absent. A solitary dog moves around in an apparently postapocalyptic landscape; prone blocks of stone trace lines. There is some greyish and clayey water and floe-like ice surfaces. Leakage of light in 16mm film colours the images at the beginning and end of the roll of film. Everything seems abandoned and alienated. It is hinted that the material extraction may have led to an environmental disaster.

Again, we hear a detached voice – we do not know from what or whom. Is it the actual material in the atmosphere as in I Am the Weather, whose surface and mass are given the ability to formulate utterances? Is it the stream of consciousness of the brown dog in profile, stoically gazing ahead? How are we to understand how a dog remembers? The closeness of the animal to the human means that we lose its contours, and the listing of things that are missed or not missed could also come from a human being. All the same one gets a hint of the sensory world of the dog, expressed by way of the human being’s arbitrary names for things: does one miss morning and evening walks but not afternoon ones? One doesn’t miss newspapers, but things made of steel and rubber.[7] Don’t miss those who smile without reason, but miss things made of leather: car seats, shoes. If this is the aftermath of the fall of civilisation, we note a sober melancholy which for the observer in the present becomes a reminder of the small joys and subjective discomforts of life. In that case the specific listing may recall the literary theorist Roland Barthes’ list published in 1977 of things he likes (and dislikes). As with the dog, the preferences are initially sensory, via the palate and the olfactory sensations – he likes salad, cinnamon, cheese, pimiento, marzipan, the smell of newly cut hair (and wonders why no one can make a perfume of it).[8] The dog sniffs its way forth to life in a way the machine will never experience.

The ongoing reassessment in our time of an anthropocentric dominance, where humanity is the absolute goal, gives art a suitable position to explore philosophical and critical issues related to the parallel life of the animals. The more instrumental approach to our relations with them can be seen in the light of among other things postcolonial theory and feminism.[9] Engagement in the non-human clears the way for a fictional potential – just think of Pierre Huyghe’s film Untitled (Human Mask) from 2014, where an ape wearing a mask and a young girl’s dress performs mechanical, learned gestures. It is apparently the only survivor after a natural disaster – with direct reference to the nuclear accident in Fukushima in 2011. Empathic awareness is one of several approaches, such being the relationship between human beings and technology – according to Donna Haraway, based not on exploitation but reciprocal adaptation. Close links between humans and animals (especially dogs) form ties of mutual influence in the interfaces between human and non-human, nature and culture.[10] How then is memory to be preserved?

The life programme of water

The unclear transitions between human beings, nature and technology – and the future that is haunted by the past – are further explored in the film Francine was a Machine (2019). Indirectly it presents the history of the automata, humanoid robots that culminate in the cyborg and artificial intelligence. The boundaries of the human shift. Marte Aas comes closer to posthumanism by way of an unconfirmed story about the philosopher René Descartes, who in the seventeenth century formulated a programme for a mechanistic understanding of physiological processes. The film takes its point of departure in Descartes and his automaton, said to be a copy of his dead daughter Francine, made of metal and mechanical components. She is discovered by the crew of a ship on its way to Sweden, in Descartes’ cabin, and thrown into the water. This odd story is linked with images recorded at a workshop in California, filmed in clear-cut tableaux. Here, ‘true-to-life’ sex dolls are made in a clinical but also craftsmanlike manner. The production of fetishised body parts is incorporated in a logic of consumption, as the images document the replication of something fundamentally artificial. Human form and machine form are customised to each other. Where does this market adaptation leave the genuinely human, the course of our lives and thoughts that extend undefined to no apparent avail?

Aas cross-cuts these scenes with abstract images of the sea where Descartes’ daughter ended up. Water as fundamental element appears as another basic projection surface, like the sky. Something may be concealed in the depths. But the water may also represent a vitalistic and flexible principle, contrasting with Descartes’ mechanistic worldview. The water is per se mutable, and the transformation contains everything. The tentacles of an octopus spread out in Aas’ film, each with its innately tactile brain as inspiration for neural and digital networks. The sea – and the body – appear as inscrutable and non-reductive vessels.

Back to earth. What does it mean to contain something?

The ongoing reassessment and upgrading of the vessel or container , viewed in the light of among other things the science fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin’s essay ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’ (1986), was manifested in 2022 in a special section of the Venice Biennale, with a number of artworks that could be filled, metaphorically and literally – eggs, baskets, nets and boxes – featuring among others artists Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Ruth Asawa. A direct line to the very first utility objects was visualised: containers to hold nuts, berries, fruit and grain were fundamental to human history. Gathering and storing became a solid, central, civilisation-building tool, often neglected in favour of sharp, long and aggressive tools – spears and swords –with a clear direction.

In the film A Letter to Zoe (2021) Marte Aas investigates container technology and shows a number of examples of storage, of among other things nuclear waste in southern Sweden, where copper canisters are located 450 metres underground, planned to be sealed for the next 100,000 years. We also see passing shots of bottle production, and a house coolly rendered in bluish colours. The house becomes a basic category for storage of occupants and inventory such as furniture, plants and vases. The container becomes a kind of body, and the opposite: the body consists of a number of units that are filled up – bladder, stomach and blood vessels. In addition the body has apertures, organs such as eyes and ears. As a classification category the container becomes manageable and permits language and computer technology. By the container a formless mass is given a contour, a definable and physical shape in the world. Its interface with the surrounding world is fundamentally porous, as leakage is always a possibility. For the body is, as we know, not sealed, but leaks and drips.

Aas’ film, which is typified by a contemplative, sometimes playful tone, is made as a monologue in letter form, addressed to the feminist theoretician Zoë Sofia, whose thoughts on the container form a central point of departure. Sofia criticises a dominant western philosophical understanding of space as something passive and feminine, by way of technological history and conventional ideas of motherhood. She demonstrates how notions of gender play a role for the features we assign to the container, greatly neglected in the narrative of the production of culture and technology. Storage and safekeeping are also processes that are active, they are interactions between container and content. Sofia (and by extension Aas) turns the focus on the containment of resources gathered in global networks with distribution as the main concern.[11] This interaction is always in motion, like the body in constant transit among potential spaces. It is in these transitional zones that Marte Aas situates her films, permeated by the leakages and crackling tensions of their elements.

[1] Dolly Jørgensen and Finn Arne Jørgensen (eds.), Silver linings – Clouds in art and science,

Museumsforlaget, Trondheim 2020, p. 9.

[2] John Durham Peters, The Marvelous Clouds – Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media,

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago/London 2015, pp.1-3.

[3] Ibid, p. 30.

[4] Donna Haraway quoted in McKenzie Wark, Molecular Red – Theory for the Anthropocene, Verso, London 2015, p. 137.

[5] https://sml.snl.no/humoralpatologi

[6] McKenzie Wark, p. 57.

[7] The text for the film is written by the author Per Schreiner.

[8] Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes, University of California Press, Berkeley/Los Angeles 1994, p. 116.

[9] Michel Pastoureau, preface in Rémi Mathis and Valérie Sueur-Hermel (eds.), Animal – A Beastly Compendium, Bloomsbury 2014, p. 13.

[10] See among other things Donna Haraway, When Species Meet, University of Minnesota Press 2007.

[11] Zoë Sofia, “Container Technologies”, Hypatia vol. 15 no. 2 (spring 2000), pp. 181-201.